A Risk Expert's Analysis on What We Get Wrong about AI Risks [Guest]

How our cognitive biases lead to faulty assessments in Risk Calculations

Hey, it’s Devansh 👋👋

Our chocolate milk cult has a lot of experts and prominent figures doing cool things. In the series Guests, I will invite these experts to come in and share their insights on various topics that they have studied/worked on. If you or someone you know has interesting ideas in Tech, AI, or any other fields, I would love to have you come on here and share your knowledge.

I put a lot of effort into creating work that is informative, useful, and independent from undue influence. If you’d like to support my writing, consider becoming a premium subscriber to my sister publication Tech Made Simple to support my crippling chocolate milk addiction. Use the button below for a lifetime 50% discount (5 USD/month, or 50 USD/year).

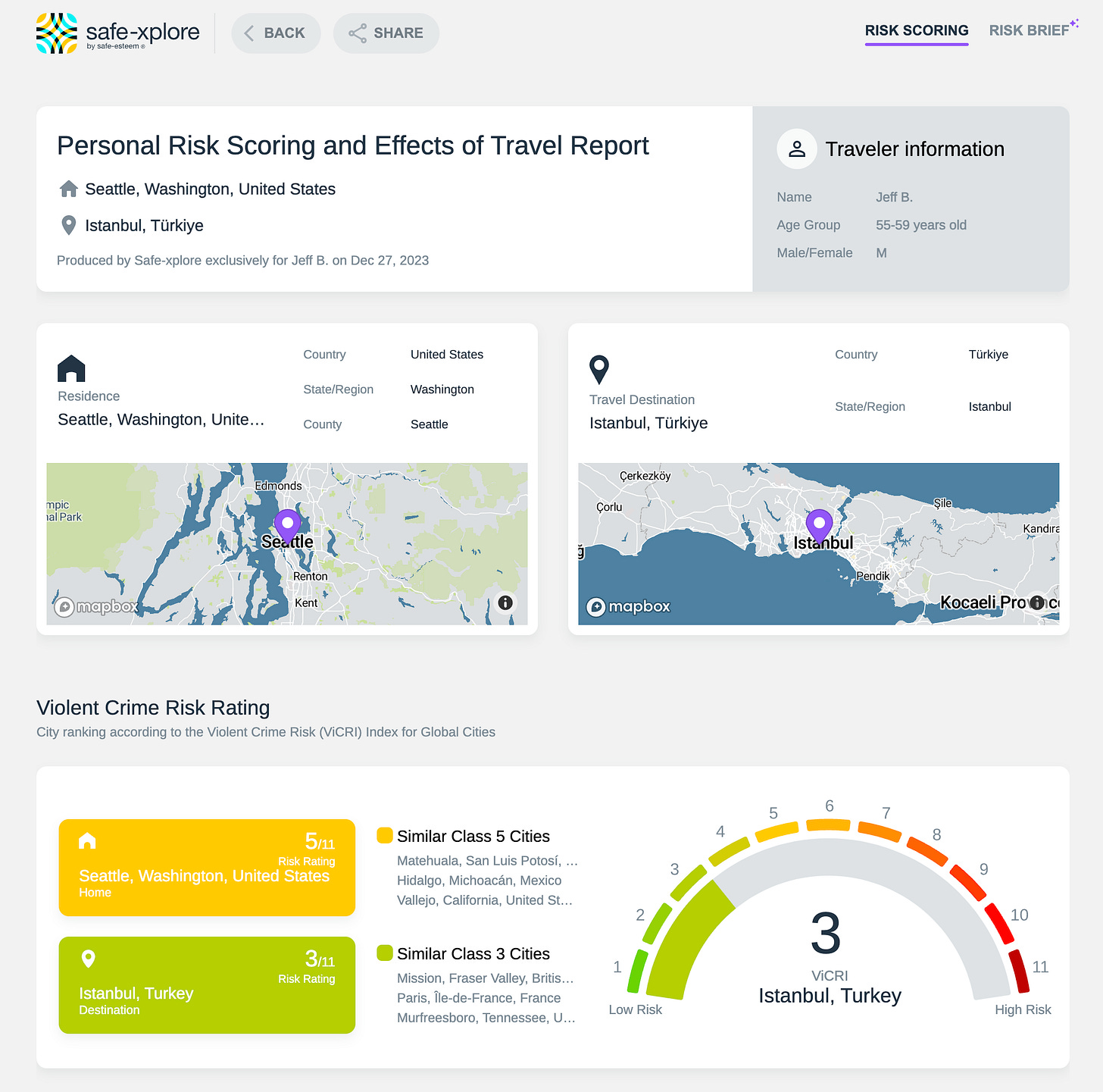

In this article, Filippo Marino goes over how our cognitive biases cause lapses in our judgment and assessments of risks. Filippo Marino is a risk judgment and decision-making expert with over 30 years of experience in both the public and private sectors. He has driven security, intelligence, and risk mitigation operations and innovation for organizations worldwide. I have learned a lot from him through our conversations about the art of predictive risk analysis, which was a whole new world for me. I highly recommend reaching out to him over LinkedIn and/or signing up for his publication Safe-esteem. We can all learn from his expertise in judgment and decision-making (JDM), and I can’t recommend his work enough.

The buzz around Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been impossible to ignore. Everywhere you look, there are bold claims about how AI will revolutionize our economy, our professions, and the trajectory of the human species. However, the technology downside or risk scenarios occupy almost as large and, unsurprisingly, a more intense portion of the conversation and media coverage.

The range of opinions is wide: from extreme predictions of a world-ending disaster to more dismissive views that brush off any concerns. In between, there are many thoughtful perspectives offering realistic insights. Amidst this cacophony, the public conversation is increasingly being framed as a duel between the Alarmists, who foresee doom, and the Accelerationists, who champion unrestrained progress. In bypassing a critical examination of the arguments from these polarized viewpoints, we risk legitimizing claims and scenarios that may lack any grounding or information value.

So, what’s the real deal? Should we brace for a future dominated by AI, resist its advance, or rethink our career plans in light of its impact?

I've spent the last thirty years helping organizations and individuals navigate various risks, building strategies to improve risk understanding and decision-making. Now, at the helm of a startup dedicated to refining human judgment in the face of risks, I want to share some of these insights with you. In this and upcoming articles, I'll highlight a number of common fallacies, aiming to provide you with a clearer, more informed perspective on how to approach this topic.

As for pandemics and COVID-19 risks, opinions about AI risk are as ubiquitous and deeply entrenched as they are susceptible to cognitive biases. Often, these views stem from the same psychological heuristics that mislead our judgments across various domains. The Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias where individuals with limited knowledge overestimate their understanding, is particularly rife in these debates.

Many assertions about AI's future are driven by the availability heuristic—our tendency to predict the likelihood of events based on what's readily brought to mind, not on objective data. Motivated reasoning, where our desires influence our conclusions, and innumeracy, a lack of comfort with numerical data, also play their parts. These factors coalesce with an apocryphal trust in gut instincts—a compelling but often deceptive guide.

When we scrutinize the chorus of voices in the AI risk debate, we find it overwhelmingly composed of software engineers, language and cognition researchers, and notably, venture capitalists and Silicon Valley influencers. Few of these commentators come from backgrounds steeped in risk measurement and quantification, risk communication, or decision science. These disciplines—alongside domain-specific expertise—are vital elements of what I term the 'risk competency tetrad.'

Learning from the OpenAI Drama

Consider the recent upheavals at OpenAI. The foundational principle behind its independent oversight board was to inject a dose of risk awareness and decision-making prudence into the organization's research and development initiatives. This was envisioned as a counterbalance to the other driving forces at play, particularly the economic incentives that can often overshadow caution and restraint in a field as dynamic as AI.

The domain of AI risks is undoubtedly more intricate and nuanced than the more straightforward decisions of hiring and firing that typify business management. The situation at OpenAI presented us with a rare and invaluable post-mortem opportunity to assess the quality of risk judgment and decision-making (JDM) exhibited by its board members, including but not limited to figures such as Helen Toner, Ilya Sutskever, and Adam D’Angelo.

At its core, risk JDM is a predictive discipline, and expertise in this area is predicated upon two foundational (meta) decisions: how to measure risk, and how to decide under uncertainty. Clearly, this board showed deep incompetence not because of the outcomes (which, in decision science, are not the meter by which we evaluate decisions) but rather because of the details later revealed about the process and rationale.

The Curse of Ambiguity and Substitution

One of the most pervasive and consequential mistakes in discussions about risk, including those about AI, is the issue of ambiguity. Ambiguous language about what is being estimated and how it is measured exploits and amplifies the natural innumeracy and feelings that shape our risk judgment. It thickens the mental fog and blinds us to the futility of these statements with little information or decision-support value.

Chief among these is the deadly ambiguity spawned by conflating threats and hazards with risks—a distinction that might seem academic but is vital for accurate discourse.

Let's clarify without being overly pedantic: threats and hazards are often the triggers or sources of potential harm. They are not, in themselves, risks. Risks pertain to the potential negative outcomes that these threats and hazards could cause. To draw an analogy from public health, consider pathogens. They are hazards, while the risk they pose translates to the likelihood and impact of resulting illness or death. Similarly, in discussions about AI, terms like proxy gaming, emergent goals, power-seeking, or unaligned behaviors are frequently and inaccurately cited as risks, when they are actually potential threats or hazards. They don't inherently include the dimension of outcome.

Why is this distinction so important? The discussion about catastrophic or existential AI risks often falls prey to a cognitive shortcut known as substitution. When people are asked to estimate the dangers posed by AI, they're not truly evaluating the probability of catastrophic outcomes; instead, they're rating how readily a scenario comes to mind—how vividly they can imagine it, which is more a measure of familiarity than likelihood. This is evident when discussing the concept of a rogue superintelligent AI, a narrative that has been popularized by various forms of media. Yet this sidesteps the critical query: 'What is the actual probability of such an AI not only coming to be but also leading to disastrous or even apocalyptic consequences?'

It's an understandable oversight; the distinction is subtle but significant. If you find yourself conflating the ease of imagining a scenario with its statistical probability, you're not alone—and indeed, you're demonstrating the very cognitive bias at play.

See: Deep Dive #1: The Airplane Analogy and How Ambiguity and Innumeracy Shape the Debate

Actualization Neglect in AI Risk Scenarios

Another way we can describe this fallacy is ‘the failure to consider the steps and dynamics needed to go from an imagined scenario to a real-world event.’ Or, at minimum, it’s a failure to acknowledge how complex and challenging it is to influence large systems.

In the domain of risk analysis, particularly with regard to complex, long-term predictions, we often grapple with phenomena that defy conventional statistical modeling—what Nassim Taleb has famously termed 'Extremistan.' These are the cases where extreme outcomes, the so-called 'black swans,' disproportionately influence the scale of impact. In such scenarios, traditional stochastic modeling approaches stumble, and scenario planning steps into the breach as a more suitable tool.

Effective scenario planning distinguishes itself from Hollywood screenwriting by either accurately estimating the likelihood of specific events through robust data analysis and statistical modeling or by pinpointing early warnings and indicators that signal the emergence of a predicted outcome. This is where the value of a post-mortem analysis becomes apparent, as it can provide solid evidence by examining similar or related events that have already transpired.

Consider the often-cited concern that AI will indelibly alter the dynamics of democratic elections, granting those with nefarious intent the power to manipulate public sentiment on a grand scale. The recent presidential election in Argentina offers us a valuable post-mortem lens. The campaign was highly polarized, with neither political side lodging significant complaints against the use of AI technologies. Notably, the Milei campaign, aligning with a global trend among right-wing populists, adopted a bold and controversial approach in its messaging, a strategy that could have been amplified by AI's capabilities.

In Argentina, there was certainly no lack of expertise or willingness to exploit AI for political gain. The generative AI tools were mature enough to be deployed effectively. The stage seemed set for AI to demonstrate its potentially disruptive power in the electoral arena. Yet, the anticipated seismic shift did not occur. The actual impact on the election's outcome was less pronounced than many had feared, and the media's focus on AI seemed to inflate its influence beyond the measurable effects.

The AI-generated images of Donald Trump getting arrested were covered by thousands of media outlets as a warning and evidence of a ‘terrifying’ future in which synthetic media would be used to disinform and manipulate public opinion. During that very same week of March 2023, the genuine Donald Trump and his proxies disseminated hundreds, if not thousands, of false statements about the US presidential elections. These were largely ignored by the media as ‘par for the course.’

It's important to remember that emotionally charged content in election campaigns is not a new development brought about by AI. While the technology has advanced, the tactics remain consistent with history. While AI has the potential to impact how elections are run, we have yet to see any radical effects of its capabilities and, more importantly, how these measurably amplify or outperform disinformation practices by real, powerful people or networks.

The Svengali Fallacy

A common pitfall in discussing AI risks is what I term the 'Svengali Fallacy' — the tendency to overestimate the power of AI to manipulate and shape human behavior through algorithms and synthetic media. This fallacy often leads to forecasts that fail to account for the practical realities of how such influence would actualize.

Yuval Harari, a renowned author and philosopher, provides a striking example of this phenomenon. He warns that the advent of Generative AI could signify 'the end of Human History'—not in an apocalyptic sense, but in the way it could usurp the role humans have played as the sole creators and disseminators of ideas, narratives, and beliefs. With the capacity to generate and distribute content more efficiently than any human, AI, according to Harari, stands to become a formidable force in the marketplace of ideas.

Some extrapolate from Harari's thesis to envision a dystopia where malevolent superintelligences—or their human acolytes—manipulate populations to establish new cults or religions, consolidating power over humanity. This speculative leap assumes AI will develop mechanisms for mass influence that outstrip our current understanding of media and communication.

How plausible is such a scenario? To assess this, we must turn to both pre-mortem and post-mortem analyses, examining historical and contemporary instances of mass communication and control. Consider the proliferation of social media platforms and the recent controversies surrounding their role in shaping public opinion. What these case studies reveal is that while technology has certainly transformed the dissemination of information, the fundamental dynamics of influence and belief formation remain complex and are not so easily commandeered, even by the most advanced AI.

These fears are directly related to the recent years’ increasing popularity of behavioral science and behavior design principles. Paired with the revelations of the Facebook troves of psychometric data and its exploitation by Cambridge Analytica in the 2016 US Presidential elections, the idea that perfectly formulated personalized messages are not only capable of steering our choices and behaviors but are already doing so at scale is often taken granted.

Although AI can potentially impact human narratives, we should not overestimate its ability to control and influence human actions and beliefs. Even the authors of some of the most heralded ‘nudging’ techniques acknowledge their limits, and much of the research in this field, whatever portion survived the replication crisis, seems to support the real but modest power of logarithmic behaviorism.

Ignorance as Moat

A prevailing theme within the narrative of AI's catastrophic potential is the belief that Large Language Models (LLMs) could inadvertently become a Pandora's Box, granting those with malicious intent the means to cause widespread harm. The argument suggests that these AI systems could discover, refine, or divulge knowledge of destructive technologies—be they advanced chemical agents, biological weapons, or cyber-weapons—to individuals poised to use them.

This argument relies on the premise that a vast reservoir of malevolence is thwarted primarily by a barrier of ignorance or a lack of access to deadly technologies. It presumes that if this barrier were breached by AI's informational capabilities, it would lead to an upsurge in large-scale atrocities.

However, most threat assessment professionals would identify this assumption as a fallacy. The reality is that the knowledge and means to inflict harm on a massive scale are already accessible. The ubiquity of firearms in certain regions, such as the United States, or the materials and know-how to construct improvised explosive devices (IEDs), are stark reminders of this. Historical precedents, like the Oklahoma City bombing, demonstrate the destructive capacity of readily available technologies. Similarly, the Tokyo subway sarin attack by the Aum Shinrikyo cult illustrates that even chemical warfare is not beyond the reach of those determined to perpetrate violence.

The notion that ignorance serves as a moat safeguarding humanity from widespread calamity does not hold up against the evidence. The means for destruction have long been within reach; the rarity of their use speaks to constraints that are social and moral rather than informational.

Motivated Reasoning

Blatant fallacies are not restricted to the alarmist side of the AI risks debate. One of the more transparent examples can be found in Alexander Karp’s New York Times Opinion piece. The CEO of Palantir Technologies is warning us here against the reluctance to engage with AI for military purposes, suggesting that such hesitance could lead to strategic disadvantages in geopolitical struggles for power.

Karp posits that the ability to deploy force and the threat thereof is foundational for effective negotiations with adversaries, implying that AI is a critical component of modern "hard power." Karp's argument suggests an 'appeal to morality,' presenting the reluctance of Silicon Valley engineers to develop AI for weaponry as a failure of national and moral duty. This framing not only simplifies a complex ethical landscape but also seems incongruous coming from Karp, who is himself a quintessential 'coastal elite.'

For someone with Karp’s education and deep familiarity with Socialist ideologies and influence strategies, these fallacies seem hardly the result of unconscious bias.

His moral appeal overlooks the possibility that these engineers may be deeply patriotic and willing to contribute to national defense in a capacity that does not involve lethal force. They could, in fact, be eager to apply their expertise and AI to strategic intelligence and decision-making tools that help avoid the kind of strategic errors witnessed in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars—conflicts that have been as disastrous for the US and the world as they have been profitable for Karp and his company.

If, as discussed earlier, the failure to provide realistic or reasonable actualization scenarios plagues many “X risks’ arguments, military applications are one sphere where such calculus seems relatively straightforward. The (partial or fully) autonomous analysis and decision optimization in high-speed, complex judgments about the use of weapon systems are here the central application's objectives. Arguments about if/when Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) will emerge and Terminator-inspired scenarios only distract us from this AI application domain's obvious, current, and measurable risk.

Not long ago, poor critical information and decision-support systems design nearly resulted in a nuclear accident. The idea of offloading tactical command and control of AI-guided weapon systems is concurrently obvious and extraordinarily dangerous. Until we are confident enough in such autonomous agents to remove human pilots from commercial planes carrying 350 passengers, it’s hard to argue we can do so for any weapon that can kill hundreds or thousands by mistake.

AI’s Role in Navigating the Epistemic Crisis

The advent of the information age has precipitated a paradox: the very tools designed to enlighten us have also plunged us into an era of misinformation, data chaos, and an emerging epistemic crisis. The gravity of this threat cannot be overstated; it uniquely undermines the bedrock of shared reality required to confront global challenges such as pandemics, terrorism, climate change, and nuclear proliferation. These threats, while formidable, can only be countered through collective action grounded in a consensus on facts and principles. In a landscape littered with 'alternative facts,' the path to resolution becomes obscured, leading to a world adrift.

It is important to recognize, however, that this crisis is not AI’s making. Its roots extend deep into the fabric of the internet, the World Wide Web, and most critically, the social networks and the behavioral incentives they cultivate.

There is no doubt that, as for any new, highly disruptive technology, AI will amplify existing risks and create new ones. Automobiles created a bank robbery boom 1920s, email resurrected the Nigerian Prince scam, and AI is already invigorating virtual kidnappings (which have been going on for decades across Latin America and a handful of countries in Africa and Asia.)

Yet, the same technology also holds immense promise. While the number of sharp, committed individuals and groups striving to combat disinformation has been growing measurably in recent years, finding effective strategies to check the spread of false information has been tough, and successes have been limited. AI stands as a potential ally in this fight. It holds the promise of bolstering our cognitive defenses, aiding in the discernment of fact from fiction, and enhancing the overall quality of information. If harnessed judiciously, AI could serve as a linchpin in the advancement of critical thinking, rationality, and informed decision-making across the spectrum of human activity.

As we stand on the cusp of what could either be a descent into informational anarchy or a renaissance of enlightened dialogue, the role of AI will be pivotal. The challenge ahead lies not in resisting the tide of technological progress, but in steering it towards the amplification of our most fundamental asset—the capacity for reasoned, informed, and collective action in the face of uncertainty.

If you liked this article and wish to share it, please refer to the following guidelines.

That is it for this piece. I appreciate your time. As always, if you’re interested in working with me or checking out my other work, my links will be at the end of this email/post. And if you found value in this write-up, I would appreciate you sharing it with more people. It is word-of-mouth referrals like yours that help me grow.

Reach out to me

Use the links below to check out my other content, learn more about tutoring, reach out to me about projects, or just to say hi.

Small Snippets about Tech, AI and Machine Learning over here

AI Newsletter- https://artificialintelligencemadesimple.substack.com/

My grandma’s favorite Tech Newsletter- https://codinginterviewsmadesimple.substack.com/

Check out my other articles on Medium. : https://rb.gy/zn1aiu

My YouTube: https://rb.gy/88iwdd

Reach out to me on LinkedIn. Let’s connect: https://rb.gy/m5ok2y

My Instagram: https://rb.gy/gmvuy9

My Twitter: https://twitter.com/Machine01776819

Are you familiar with Didier Sornette’s risk analysis works at ETH?

Here is a link to his publications.

https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=HGsSmMAAAAAJ&hl=en